Humpbacks, Mola Mola, White Sharks and Calm Weather

The winds, weather and waters in the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary have been strangely shifting, prescient of the impending El Niño for the fall of 2023. This year we have been lucky, ducking between strong and cool north westerlies and unseasonable low-pressure systems with rain, providing us with flat calm days in the gaps: a rarity in the Gulf of the Farallones. Called the Islands of the Dead by the local native-Americans, these normally fog-shrouded islands are clear in detail, and have even been visible from shore this month.

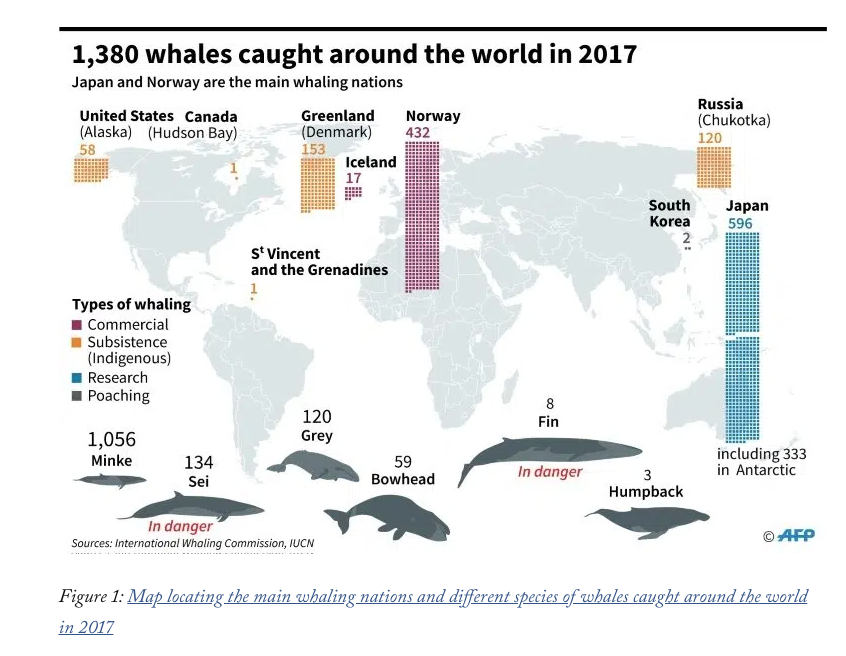

Without wind, the soaring seabirds such as shearwaters and fulmars are “grounded,” floating and diving on anchovies from the surface. Even the whales seem placid, dispersed among the patches of anchovies, singly feeding nearshore instead of in groups. On our first visit with guest Naturalist James Moskito of Ocean Safaris, we saw Parasitic Jaegers harassing feeding Fulmars, a tube-nosed bird related to the Albatross, and what appeared to be a Minke whale in the swell (Balaenoptera acutorostrata scammoni), with their distinctive dark body and white sided patch. Minke whales are members of the baleen whale family and are the smallest of the rorquals. One of the more abundant whales in the world ocean, we rarely see these in the Sanctuary. They are also a species still killed commercially in numbers by a few countries.

Aside from one trip with no wind, but a rolling NW swell, the trips have been sunny with patches of fog and a slight breeze: good for spying whale blows on the horizon. The most abundant whale in the Sanctuary this time of year is the humpback whale (North Pacific subspecies Megaptera novaeangliae kuzira). Humpbacks are common here in the spring through winter after migrating north from two areas: one off Mexico and the other near Central America. The whales come to feed on the anchovies and other forage fish in the Gulf of the Farallones, abundant because of the rich phytoplankton (single celled plants) and zooplankton (small shrimp and other crustaceans) which make up the base of the food chain. The rich seawater upwelled from the deep waters, feeds this proliferation of plankton, attracting marine life from across the Pacific into our Sanctuary waters, including seabirds, whales, and other marine mammals.

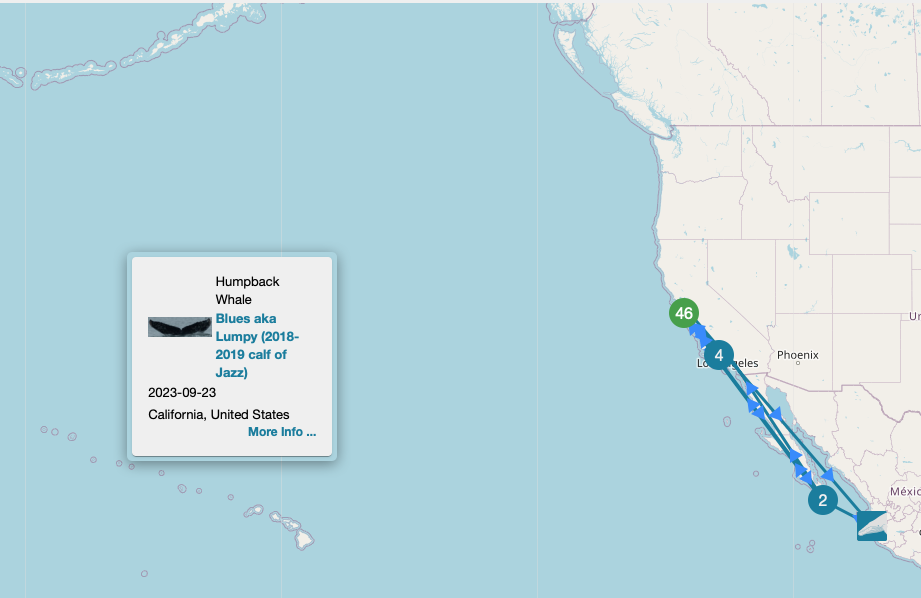

Like the dorsal fin of white sharks, the underside of a whale’s flukes (tail fin) is like a fingerprint, with unique patterns that are identifiable. Photographs entered into a database can be matched over time, eliciting information on individual movements, migration and behavior. This data, once contributed only by scientists can now be added by “Community Scientists”, amplifying available information. The data analyzed by scientists from Cascadia Research and NOAA can infer whale movements, densities and even risk, and is valuable for understanding and protecting whales.

With her recognizable pattern, we photographed one whale fluking and feeding near the shipping lane, and entered the image into the scientific database Happy Whale. The last time this whale had been recorded was five years ago in Monterey. We spotted the same whale three trips later feeding nearshore. On some whales we observe healed scarring from a ship-strike, or parallel scars from propellor damage. The locations we record will help determine threats to these whales from the busy shipping lane nearby. If we see an entangles whale it will be reported to the NOAA’s Marine Mammal Health & Stranding Response Program’s with the Marin Marine Mammal Center for an immediate response to remove the gear. Once hunted to near extermination, humpback whales have recovered and number nearly 5,000 in this population. The humpback whales visiting our Sanctuary are defined as the California/Oregon/Washington Stock which includes whales from two feeding groups: the California-Oregon and Southern British Columbia – Washington (SBC/WA). The California- Oregon stock is composed of populations that winter in Mexico, and a separate group that winters off the coast of Central America.

Humpback fluke with identifiable pattern. Image Courtesy Cynthia Ariosta

When industrial whaling ended, the establishment of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) in 1946 intended to provide for the conservation of whale populations that had been hunted dramatically. Also intended for the development of the whaling industry, the IWC became increasingly conservation oriented, and gave whales a chance for recovery. In 1972, the U.N. Conference on the Human Environment passed a resolution calling for a ten-year moratorium on commercial whaling. In 1979, the IWC banned the hunting of all whale species (except minke whales) by factory ships, and declared the entire Indian Ocean as a whale sanctuary. In 1982, the IWC adopted an indefinite global moratorium on commercial whaling, and a full moratorium by the United Nations (three countries Japan, Norway and Iceland still kill whales selectively).

With the cessation of whaling, the population of California Gray Whales (Eschrichtius robustus) and the Northeast population of humpback whales have recovered from endangerment. However, malnutrition caused by food shifts, climate change and habitat loss still threaten these species. This is being evidenced by a series of Unusual Mortality Events (UME) impacting the Gray Whales, reducing their population by as much as 25%. The most recent estimate of the population of Gray Whales in winter 2022/2023 is 14,526. This new estimate is roughly comparable to the number of gray whales when counts first began in the late 1960s according to NOAA. Gray whales undergo one of the longest annual migrations between the birthing and mating areas in Baja CA Mexico and feeding grounds off Alaska, a round trip of up to 12,000 miles. Another group, known as the Pacific Coast Feeding Aggregation do not migrate, instead feeding along the coast. In the past, we have seen these short-term residents near the Farallon Islands, and we search for the distinctive heart-shaped blow when we visit. Often we observe these short-term resident whales feeding in the sediments south of the island near the shallow area called Fanny Shoals.

California Gray Whale with barnacles and whale lice. Image David McGuire

Orcas also pass through the Gulf, and occasionally prey on humpback and gray whale calves or sick whales. This June, a large pack of 24 Bigg’s killer whales (or Transients) were observed hunting by the Farallones. This month a small group was observed swimming south towards Monterey, where a predation event on a gray whale has been documented this summer. Orcas have 10 different genetic groups known as Ecotypes, that have different and sometimes overlapping, feeding grounds and behavior. The orcas passing through the Sanctuary are primarily, the Biggs Ecotype, known for their efficient hunting of other marine mammals. Other ecotypes include the endangered Resident ecotype (primarily feeding on salmon), and the Offshore group. This week, three orcas from the Offshore group were observed feeding on what may have been a white shark off the Monterey Canyon. Although we were on the look out for the remarkable dorsal fin and behavior of the Orcas, we are relieved they are not near the island, where historically predation on white sharks (and subsequent evacuation of SEFI waters) has been observed. See the Whale that Ate Jaws.

Much of the focus of whale mortality off our coast has been entanglement in fishing gear: lobster pots in the south and crab pots north of Point Conception. The beloved dungeness crab is the darling of Fisherman’s wharf, and was once considered the San Francisco treat during the Thanksgiving holiday in the Bay Area. To capture these delectable crustaceans, a circular steel cage is lowered to the bottom with polypropylene rope attached to an identification buoy and a float. Whales risk entanglement in the gear, fatiguing them, causing damage and in some cases death. Along with the feeding humpbacks, each year in spring the gray whales migrate north. In the late months of summer/fall the gray whales pass southwards, while the Humpbacks remain to feed, at risk to entanglement with fishing gear. Seasonal closures to the commercial crab fishing have reduced the risk of entanglement, but they are also shutting down a domestic fishery, while ignoring a larger cause of death.

At greater risk to whales is from the 7,000-plus ships that enter and exit the San Francisco Bay each year. Many of these large container ships are over 1,000 feet, traveling at speeds in excess of 25 knots striking, severely injuring and killing whales, often without even knowing they have snagged a cetacean on their bulbous bow.

Each year, close to 100 whales are hit and killed by ships along the West Coast – many of them near San Francisco. From 2011 to 2021 an average of 10 whales a year along the West Coast were officially recorded as being struck by vessels, and not all of those whales died, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. However, for every whale death recorded many whales are killed or injured, unobserved and unrecorded. The list includes gray, minke and sei whales in addition to other endangered whales.

Since 2013, there has been a voluntary vessel speed reduction to 10 knots (about 11 mph) in place for large ships in the three shipping lanes that project from the Bay, but only from May to November, during whale migration season. However, like in 2022, humpback whales have remained outside the Bay well into December. Not all companies observe the slow down, and we see ships traveling 20-25 knots traveling towards the traffic separation scheme where whales are observed feeding.

According to projections by the Petaluma organization Point Blue Conservation Science, as many as 83 endangered whales, humpback, blue and even rare fin whales, are killed by ships on the West Coast each year. But because their carcasses sink quickly, only a fraction are seen and reported, the scientists conclude. Many whales swim with twisted vertebrae and scarring evident of a ship-strike, and several wash ashore in a severely decomposed state, making it difficult to confirm the absolute cause of death.

Deadly ship strikes can be most easily solved by ships reducing their speed in known whale habitat, especially feeding zones. NOAA issues seasonal voluntary speed reduction requests within its West Coast national sanctuaries with the goal of reducing the risk to whales. In the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary to the south off Santa Barbara, ships transiting the channel were responsible for killing scores of whales including endangered blue whales. A program titled Blue Whales and Blue Skies between NOAA, the Sanctuary and shipping companies negotiated a speed limit below 14 knots, resulting in reduced whale mortality and the added benefit of reduced air pollution emissions from the ships. Mandatory speed reductions of ships in the Sanctuary waters would help us better protect whales, with the added benefit of decreased air pollution, and would protect other surface marine life.

On the Sunny Side

Aside from the abundant container ships and humpback whales, this has been a most remarkable year seeing the giant ocean sunfish, or mola mola.

The ocean sunfish, is one of the largest bony fish in the world. The body length of adults can reach 3.3 meters (14 feet) typically weighing between 500 and 2,205 pounds. Sunfish look like a giant swimming head without a tail. They are often observed at the surface, lying on their sides with large dorsal and anal fins flapping gently. The body is flattened laterally, and nearly oval in shape. Weak swimmers, the sunfish are themselves considered plankton and cannot avoid being run over by ships and boats. Here to feed on salps and jellies, the adults spawn in the spring, and in the fall, we see schools of baby sunfish the size of dinner plates finning at the surface.

At the island, biologists with Point Blue (formerly Point Reyes Bird Observatory) keep watch from the old lighthouse, recording the bird and pinniped population, as well as people who enter the Sanctuary waters near the island. They have also resumed the white shark observation program, recording predation events. Cruising by SEFI on our second trip, Point Blue announced on the radio observing a predation event near the island that morning. We didn’t see a white shark on that trip, but we did see a blue shark. With sea surface temperatures in the low 60 degrees F, we are seeing more of these pelagic sharks this year.

On our last trip, we followed the Bonita channel north, turning west before Duxbury reef searching for the whales that have been feeding inshore. This year the forage fish have been shoved by currents and winds close to the coast, and dispersing the food. Instead of mid channel, many of the whales we have seen are nearshore, and a few miles out we were not disappointed. A pair of whales exhaled their recognizable blow, lingering long in the light breeze. The whales were randomly feeding with shallow dives and direction changes, but our watchers got great views, with one clearly identifiable fluke photo. This juvenile whale has been named “Blues”, first observed in Mexico, and later in Monterey and twice on our trips in the Greater Farallones.

At the island, the observers on the hill again reported seeing a predation event. We deployed our Trident ROV from the stern in Mirounga Bay to look at bottom life and fish, when Captain John shouted ‘Shark!” Along a scum line between Indian Head and Saddle Rock, a white shark surfaced off the bow, and quickly disappeared. Recovering the ROV we motored closer as the passengers on the bow were treated to two sightings of a white shark dorsal and upper caudal (tail) fin. Later we approached two gulls tugging on an entrail, the remnants of the “Landlord’s” morning snack, like fighting over a piece of spaghetti.

As leaders in the California Marine Protected Area Collaboratives, we use these trips to educate the public as well as fishermen about the importance of marine protection, and the effectiveness of our state MPA system, including at the Farallones. We also use our Trident ROV to observe and record wildlife in the state and Sanctuary waters. Now a no-take marine reserve, we are seeing more rockfish and the beautiful benthic habitat at Southeast Farallon Island (SEFI) flourish.

More than just shark and whale trips, ecotourism trips like these educate as well as contribute to science and conservation. We lead these unique trips each Sharktober when the white sharks return from their amazing migration of nearly 5,000 miles round-trip to forage in our National Marine Sanctuary. As part of NOAA’s National Marine Sanctuary White Shark Stewardship program, we collect data using photographs and observations on whales, seabirds and white sharks while educating the public on the importance of white sharks – and all life in the ocean.

These unique natural history trips to the Devil’s Teeth, (the Island of the Great White Shark) focus on the history, geology and biology of the Greater Farallones and San Francisco Bay. We only book in fall when the white sharks return and the weather is clement for our passengers and students. We focus on shark conservation and the health of the entire marine ecosystem in our sanctuary. Although we will watch whales and seabirds, and seek sharks- these trips are conservation and marine education experiences.

Sources

Andrew, R. K., B. M. Howe, J. A. Mercer, and M. A. Dzieciuch. 2002. Ocean ambient sound: comparing the 1960’s with the 1990’s for a receiver off the California coast. Acoustic Research Letters Online 3:65-70.

Barlow, J., J. Calambokidis, E. A. Falcone, C. S. Baker, A. M. Burdin, P. J. Clapham, J. K. B. Ford, C. M. Gabriele, R. LeDuc, D. K. Mattila, T. J. Quinn II, L. Rojas-Bracho, J. M. Straley, B. L. Taylor, J. Urbán R., P. Wade, D. Weller, B. H. Witteveen, and M. Yamaguchi. 2011. Humpback whale abundance in the North Pacific estimated by photographic capture-recapture with bias correction from simulation studies. Mar. Mammal Sci.27:793-818

NOAA Pacific Marine Mammal Stock Assessments 2021 HUMPBACK WHALE (Megaptera novaeangliae):

California/Oregon/Washington Stock Revised 3/14/2022

NOAA Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae kuzira)

Central America / Southern Mexico – California-Oregon-Washington Stock Revised 5/30/2023 (New SAR)

Baker, S. et al Strong maternal fidelity and natal philopatry shape genetic structure in North Pacific humpback whales December 2013 Marine Ecology Progress Series 494:291-30 DOI:10.3354/meps10508‘

Andrew J. Read, The ecology of whales in a changing climate, Science, 382, 6667, (159-160), (2023)./doi/10.1126/science.adk4244

Joshua D.Stewart, Joyce, T.W., Durban, J.W., Calambokidis, J., Fauquier, D., Fearnbach, D., Grebmeier, J.M., Lynn, M., Manizza, M., Perryman, W.L., Tinker, M.T., & Weller, D.W., 2023. Boom-bust cycles in gray whales associated with dynamic and changing Arctic conditions. Science 382, 207-211.doi: 10.1126/science.adi1847.