A 2024 study of shark fins in Singapore using DNA bar-coding technology has revealed a large deficiency in accurate labeling of shark fins, with an alarming presence of protected and endangered species in the Singapore fin market.

Singapore is a globally significant trade hub of wildlife products and is a major importer and consumer of shark fin. A study of fin trade between 2005 and 2014 revealed that Singapore was the world’s second largest importer (14, 114 tonnes) and re-exported (12,405 tonnes) of shark fins globally. In that study, the researchers found five species protected under CITES including the basking shark, oceanic whitetip shark, scalloped hammerhead shark, and the porbeagle shark.

Shark fins are the staple ingredient of the delicacy shark fin soup consumed throughout Southeast Asia.

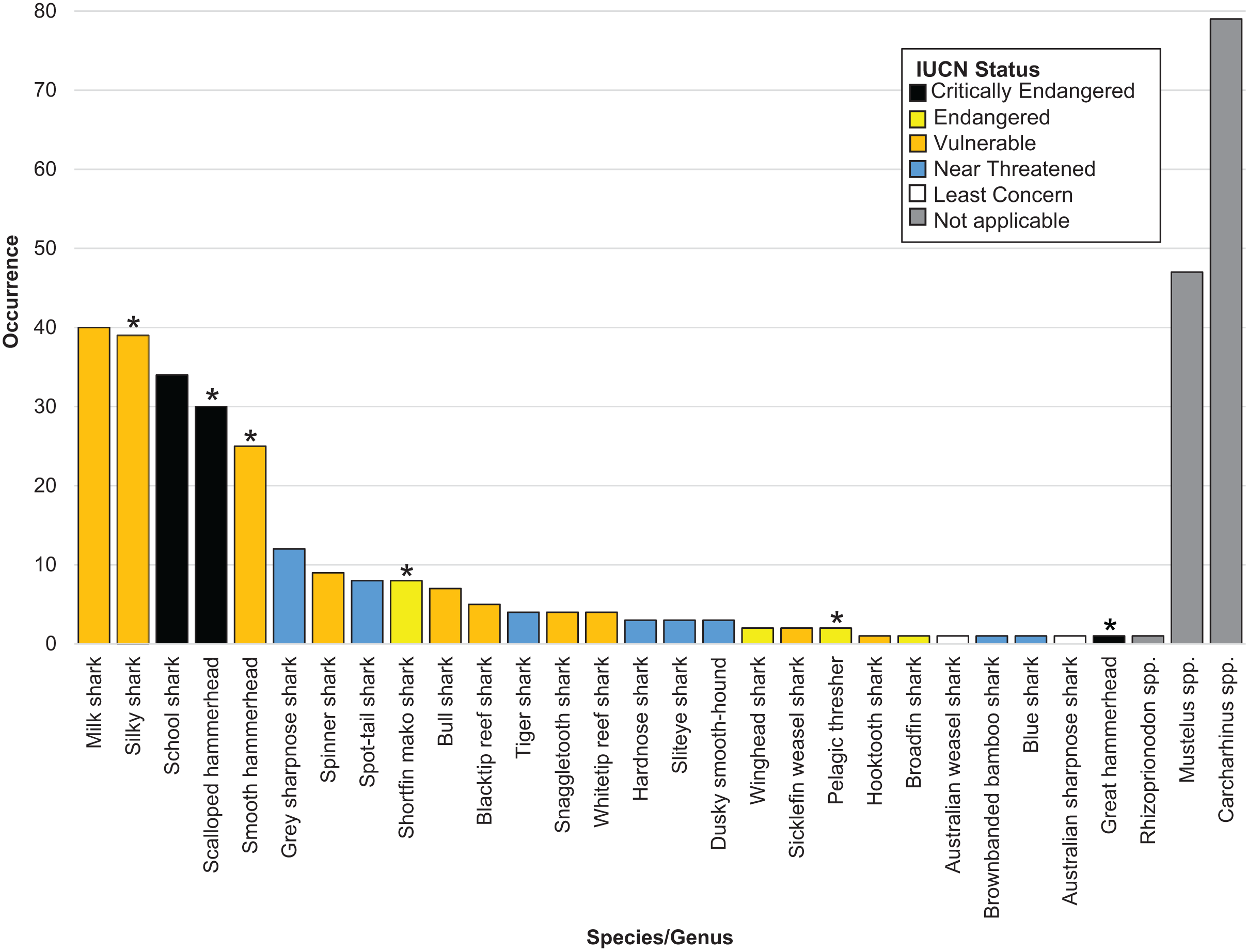

The recent study, conducted by the National University of Singapore, the researchers Shen et al., collected 505 shark fin samples from 25 different local seafood and Traditional Chinese Medicine shops. Through DNA analysis, the team identified 27 species of shark, with three species listed as Critically Endangered, four as Endangered, and ten as Vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

The researchers reported that the top five most frequently encountered species are the Milk shark (Rhizoprionodon acutus), Silky Shark (Carcharhinus falciformis), School Shark (Galeorhinus galeus), Scalloped Hammerhead (Sphyrna lewini), and the Giant Hammerhead (Sphyrna zygaena). Milk sharks are a widely distributed, nearshore, Requiem shark, with concerns of overexploitation. The other top four species represented are all listed as critically endangered by the IUCN. Scalloped Hammerhead and the Great Hammerhead are both listed under CITES* Appendix II requiring, extensive reporting and permitting to export or import. School (or Soupfin) sharks are Threatened and experiencing a severe global decline in population.

Silky sharks are critically endangered, a CITES II protected species, and vulnerable as bycatch. This species has suffered a global decline in population between 70 and 90%. In all, six species in the study were listed on CITES Appendix II, meaning that the trade must be controlled in order to avoid overfishing or risk of extinction.

Shark Species Ranked From Fins Sampled in Shen et. al. (2024). Stars denote CITES (trade) protection.

Most of the re-exports of shark fin from Singapore go to Hong Kong and mainland China. A 2022 study in Hong Kong, the world’s largest shark fin trade hub, reported that two-thirds of the sharks involved in the global fin trade are at risk of extinction, or come from populations that are in decline. Shark fins within the trade are commonly exported in dried forms and sold under vaguely generic terms without species designation, such as “shark fin” or “dried seafood”. This ambiguous or deliberate obfuscation of labelling makes enforcement and monitoring of the trade challenging, and allows for the trade of protected species.

All dried fins collected in the Singapore study were sold under the generic term “shark fin”. This vague labelling prevents accurate monitoring of the species involved in the trade, and allows for the illegal traffic of prohibited species undermining management and conservation. Inaccurate labeling can also expose unwitting consumers to unsafe concentrations of toxic metals the authors note. Pelagic species of sharks have elevated levels of mercury and other metals. Consumption of shark fins can pose health risks to consumers when toxic metal concentrations are above the established safe limits in shark fins.

Once a shark’s fin is removed and dried, identifying the species by sight alone is difficult or even impossible. Most species in the study were from the Requiem family, in the genus Carcharhinus, a very large group with many threatened species. The close genetic profiles make species designation difficult to identify, thereby allowing trade in species that may be threatened, such as reef sharks. The life history of sharks and the challenges associated with regulating fisheries and the fin trade make sharks vulnerable to overfishing. Identification by species adds one more level of difficulty once the fin is processed and in the trade.

As a signatory to CITES, Singapore is obliged to prevent and monitor the trade of regulated species. Accurate labelling and better accountability in the supply chain can protect endangered sharks and protect consumers from toxic metals. The government of Singapore must do a better job regulating trade by requiring increased tracking and labeling, and observing international conservation policies they have committed to, to protect endangered sharks.

We are calling on the government of Singapore to adhere to CITES agreements regarding shark fin, stop import/exports of protected species and increasing better labeling and tracking of shark fin products.

SOURCES

Selena Shen K, Cheow JJ, Cheung AB, Koh RJR, Koh Xiao Mun A, Lee YN, Lim YZ, Namatame M, Peng E, Vintenbakh V, Lim EXY, Wainwright BJ. 2024. DNA barcoding continues to identify endangered species of shark sold as food in a globally significant shark fin trade hub. PeerJ 12:e16647 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.16647

Boon Pei Ya 2017. Shark and Ray Trade in Singapore. TRAFFIC Publication date: May 2017.

Cardeñosa D, Shea KH, Zhang H, Feldheim K, Fischer GA, Chapman DD. 2020.Small fins, large trade: a snapshot of the species composition of low-value shark fins in the Hong Kong markets. Animal Conservation 23(2):203-211

Cardeñosa D, Shea SK, Zhang H, Fischer GA, Simpfendorfer CA, Chapman DD.2022. Two thirds of species in a global shark fin trade hub are threatened with extinction: conservation potential of international trade regulations for coastal sharks.Conservation Letters 15(5):e12910

Choy PPC, Wainwright BJ. 2022. What is in your shark fin soup? Probably an endangered shark species and a bit of mercury. Animals 12(7):802

*CITES works by subjecting international trade in specimens of selected species to certain controls. All import, export, re-export and introduction from the sea of species covered by the Convention has to be authorized through a licensing system. Each Party to the Convention must designate one or more Management Authorities in charge of administering that licensing system and one or more Scientific Authorities to advise them on the effects of trade on the status of the species. The species covered by CITES are listed in three Appendices, according to the degree of protection they need. (For additional information on the number and type of species covered by the Convention click here.)

Appendices I and II

Appendix I includes species threatened with extinction. Trade in specimens of these species is permitted only in exceptional circumstances.

Appendix II includes species not necessarily threatened with extinction, but in which trade must be controlled in order to avoid utilization incompatible with their survival.

Appendix III

This Appendix contains species that are protected in at least one country, which has asked other CITES Parties for assistance in controlling the trade. Changes to Appendix III follow a distinct procedure from changes to Appendices I and II, as each Party’s is entitled to make unilateral amendments to it.