Sharktober is a time to observe, record and celebrate white sharks through science and education.

Surfers and divers along the central and northern California coastline have long been aware that large great white sharks (white sharks) are observed and encountered most during the fall months. Scientists such as California Academy of Sciences researcher Dr. John McCosker have also documented a significantly larger rate of encounters with humans (>50%) in what is called the Red Triangle during these months. Peaking around October, we call these months of higher observation and encounters with white sharks “Sharktober”. As early as the 1980s, researchers at the Farallon Islands Dr. Peter Pyle and Scot Anderson recorded large white sharks arrive in late summer, and feeding in spectacular predation events on the pinnipeds that gather to mate and feed. Identifying these sharks via matching photographs of dorsal fins, these scientists were able to identify individuals and document their disappearance each winter, and return the next year. This includes the now famous shark Tom Johnson, first observed in 1987 and tracked across the Pacific and back again.

Tom Johnson (TJ) is the longest studied white shark in the world. Numerous photographs and several electronic tags have been used with this shark as technology has developed over the past few decades. A satellite tag on TJ in 2004 was one of the first to show that white shark males regularly migrated to the white shark Cafe in the central north Pacific, between California and Hawai’i. Smaller scale acoustic tags have shown that Tom’s regular hunting grounds are around SE Farallon Island and Tomales Point in Marin County.

In 1987 Tom’s length was recorded to be at least 13 feet long, and today measures nearly 17 feet. Since white shark males mature between 10 and 12 feet, long term tracking and observations of Tom have proven that white sharks are very long lived. A study published in the journal Marine and Freshwater Research suggested males take 26 years to reach sexual maturity, whereas females aren’t ready to have babies until they’re about 33 years old, much later than originally estimated. This would make Tom well over 50 years old. That study also showed that white sharks can live over 30 years and possibly as much as 70 years. Tom disappeared for several years and it was feared he might have been lost to fishermen in the open sea, but Tom re-appeared two years ago. Now thats a good reason to celebrate Sharktober!

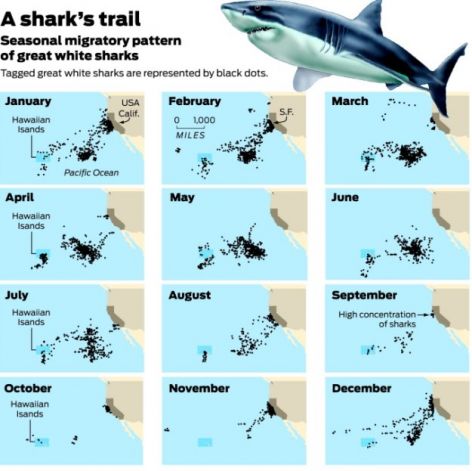

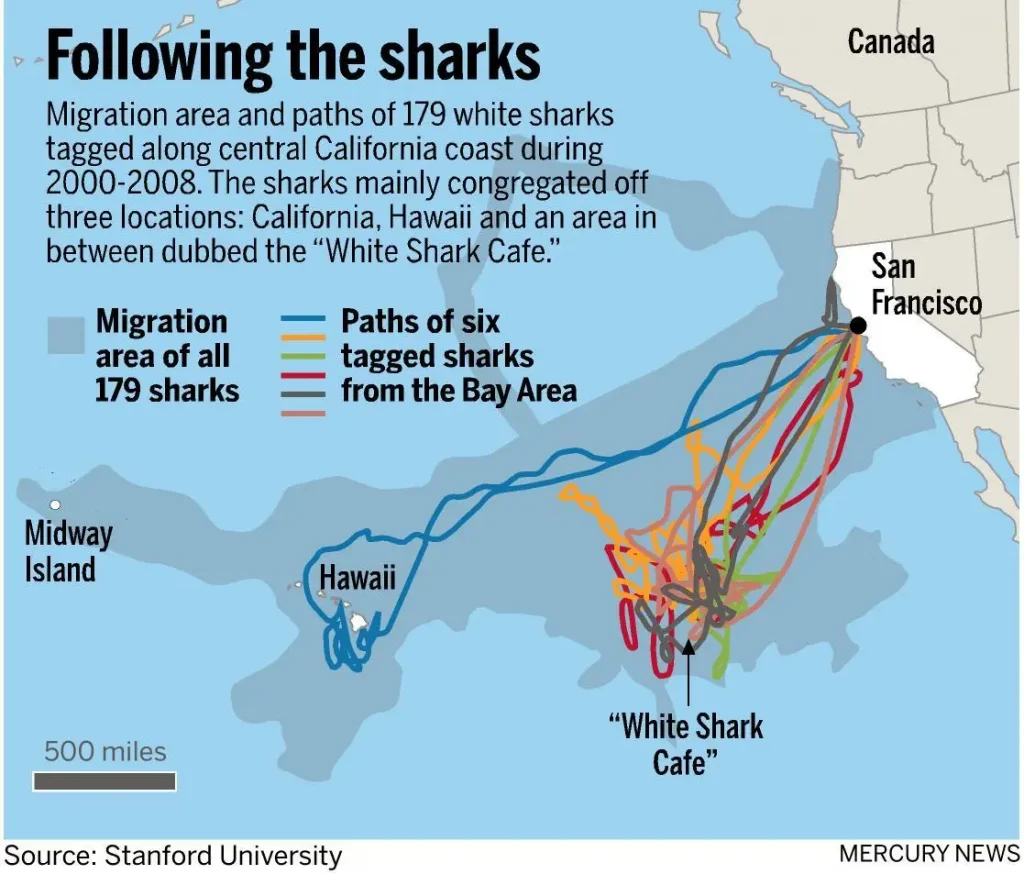

Not until satellite tracking data from sharks tagged by the Block Lab at Stanford’s Hopkins Marine Lab and the Monterey Aquarium did we realize where and when the large white sharks swimming off our coastline go, and when they return. Stanford’s Tagging of Ocean Pelagic Predators (TOPP) team started tagging sharks using pop-up satellite (PSAT) tags around 2005. Tracking the transmissions received from the tagged sharks, TOPP learned that the large sharks leave our coastal feeding areas in the winter months and swim westwards, offshore to what is called the White Shark Cafe. Using tags transmitting a year or more, the scientists have demonstrated that in late August and early September the mature white sharks return to our coastline after an incredible migration over 2000 miles west in the open ocean, and some from as far as Hawai’i!

White Shark Cafe’ to the Devils Teeth

This region a few hundred miles off Hawaii called the White Shark Cafe, serves as a mixing area between the white sharks off Ano Nuevo and Guadalupe Island. From diving profiles it looks like they are feeding, possibly on giant squid but also on the elephant seals that migrate in the same direction, and they may be breeding there. This region is on the high seas where there are very little protections for these and other sharks, particularly from the depredations of the shark fin trade.

Some sharks have been tracked traveling as far west as the Hawaiian Islands and in 2022, a mature female white shark was photographed off the main island of Hawaii for the first time! Swimming steadily at the rate of 80-100 miles/day, these majestic predators return to our coastal points and islands to feed, especially the Farallon Islands where some of the largest white sharks are observed.

SHARKTOBER AND SHARK ATTACKS

The increase in large white sharks in the late summer/early fall correlates with the pupping season of their favorite prey- northern elephant seals and other pinnipeds (seals and sealions). Hot spots of white shark activity occur around these seal colonies e.g. the Farallones and Pt Reyes, Ano Nuevo, and the Channel Islands. Human- white shark interactions (often termed attacks) also increase during these months. We prefer to call these events encounters or interactions, and not attacks, which has the connotation of malicious pre-meditation. Dr. John McCosker of the California Academy of Sciences hypothesized that bites on surfers and divers are mistaken identity and occur because we resemble their favored prey from beneath. White sharks predominately approach their prey from beneath, and bite their prey near the surface with explosive power in what is termed ambush behavior. Although this has been disputed (some bites do occur in shallow water,) testing using objects at the surface by Scot Anderson and later Dr. Peter Pyle at SE Farallon Island have supported this hypothesis. With a wounded seal, the shark will circle and then consume the prey once they have weakened. With humans, after white sharks have released the victim, they rarely will return to bite again. On the west coast of North America, approximately 90% of the victims of these “bite and spit” incidents survive.

Yes, water enthusiasts should practice caution- especially around seal colonies during the fall months. Surfing or diving in buddy pairs is advisable. Shark Stewards is developing a warning system on social media when sharks are seen near the coast or there are encounters using the hashtag #SharkWatch. The shark watch community science database also collects data on observations of living sharks (not just white sharks), fishing and encounters in California. The goal is to provide an alert network, increase public safety and develop recommendations to reduce shark encounters and harmful fishing. We can, and we must coexist with these important, and increasingly threatened ocean predators.

How Many Great Whites are There?

As with many sharks, we don’t know how exactly how large the great white shark population is. Many historical population estimates of sharks come from fishing. Fishing records suggest that the Northeast Pacific population prior to industrial fishing was greater than now, but we don’t know what that level was. Sharks are very difficult to study and count. One recent study based on photographic observations and a statistical model suggests less than 300 adult and sub adult white sharks in the two major aggregations in California. Coupled with a similar prediction of about 100 off Guadalupe Mexico, this original estimate placed the entire population of mature sharks at less than 500 individuals in this geographically isolated population.

Although this doesn’t include baby and young sharks, and the sharks that are not mature enough to migrate, it suggests the Northeast Pacific population is small. A 2022 study by Dr Paul Kanive and others documented 350 sharks in the north central population, and considers this a fairly healthy and robust population compared to the other aggregations globally. Work contributed by citizen scientists and Mexican scientists have documented over 350 individuals over time in the Guadalupe sub-population. Combined with the more abundant juvenile and sub adult shark cohorts off southern California and Baja, the northeast Pacific are growing thanks to strong protection while in state and federal waters.

This rise since the 1980s is due to listing as an Endangered Species, state and federal protection, as well as the removal of gillnets in the birthing and nursery area of southern California. It is also associated with the increase in prey population including whales, sea lions and seals.

Although we know this population has had impacts from fishing, and is still experiencing losses in the last remaining gill net fishery off the California coastline (we are advocating for elimination) and Baja California. Once offshore these sharks are also prey to longlines set for tuna and the depredations of the shark fin trade.

These and other species of sharks are still killed at an unknown rate in Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) fisheries, and population numbers are inexact. It raises conservation concerns, because as apex predators, sharks are critical for the balance and health of fish and marine ecosystems. We also know that most populations of large sharks have plummeted in the past 50 years, and many species are threatened or endangered. Globally it has been estimated that all white sharks number around 3000-5000, with perhaps 1500 in our population in the Northeast Pacific. At any one point there may be only a score or so of these adult sharks around the feeding areas, which is not many and makes them vulnerable to habitat loss, pollution or poaching.

What really is Sharktober then?

Most of the human- white shark encounters occur in our area during the fall months and the press generates a lot of negative attention, so we decided to celebrate, not hate sharks and branded our outreach efforts Sharktober. This is a month-long celebration of white sharks, but really all sharks. In 2008, Shark Stewards launched our annual Sharktober campaign, hosting Sharktoberfest education efforts to celebrate the return of the white sharks to our Sanctuary offshore, and to educate and motivate the public to protect sharks. The first campaign was to drive support for the successful California Shark Fin Ban, and the establishment of California marine protected areas in 2009. Since that time we have used these events with our partners at the California Academy of Sciences, the Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, the California Coastal Conservancy and other NGOS and agencies to reach over 100,000 public and youth directly in the Bay Area and beyond.

Shark Stewards focuses on celebrating the return of these sharks, educating the public on the importance of these sharks to marine ecosystems, and working together to protect sharks and all marine life. We use Sharktober to turn the negativity of the press and the poor impression the public has about white sharks and instead try to bring awareness around the importance of sharks to marine ecosystems, and why we should protect them.

Over 70% of the ocean’s sharks have been fished out and one third are threatened with extinction. During Sharktober we celebrate the return of white sharks and use them as a symbol to help save lesser known sharks and rays from extinction.