One of the more breathtaking experiences I have had with sharks was to watch a tiger shark appear from deep, dark water at dusk. Hovering at one hundred feet, my friends drift with me waiting in the oncoming darkness, searching for their first tiger shark. Suddenly, a pale dot rises, quickly transforming into a blunt snout ahead of a twelve- foot fish. She loops lazily as one large black eye scans us, as we pan the pregnant female with our cameras. Splendid bars adorn the thick gray body, and she almost hangs suspended as she examines us, and then with a kick of her powerful lunate tail, this perfect predator disappears away into the depths.

Tiger sharks, (Galeocerdo cuvier), are countershaded, with a gray to a blue-green dorsal surface with pale underbellies. Tiger sharks are named for their distinctive color pattern with dark gray vertical “stripes” and a spotted pattern on the flanks with a pale underside. The markings known as bars (not stripes) are especially distinctive in juveniles but fade with age. They have sharp curved teeth with pronounced serrations and sideways pointing tips they use to saw flesh from their prey. Tiger sharks also have long fins with a large asymmetrical tail.

A large bodied shark, most tiger sharks are between 10 and 14 feet, although much larger individuals are observed. On average, they weigh between 400 to 1400 pounds. The largest specimens attain lengths of over 18 ft, and are estimated to weigh over 2000 lbs. Males reach sexual maturity at 7-9 ft, while females mature at 8-10 ft, taking 7 – 8 years to mature, respectively. Mature females give birth every 3 years with a 16 month gestation. Once considered to live around 25 years, new observations suggest they can live much longer. The young develop internally and are birthed live, with litters ranging from 10 to 80 pups.

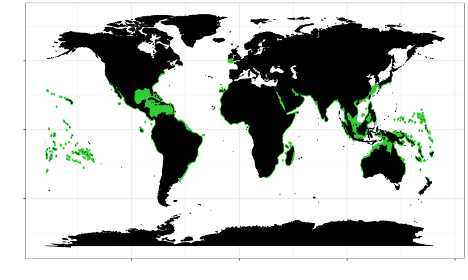

Populations are found across the globe in most tropical and temperate waters except the Mediterranean. Individuals have been tracked across oceans but are also localized on reefs and near rivers in tropical and subtropical waters. They are common around the central Pacific islands, including the Hawaiian islands where they are relatively common.

Tiger sharks have also been recorded in temperate waters near Japan, Italy, the Red Sea, and New Zealand, although less common. While close to the coast, they live in deeper waters near coral reefs, and forage in shallow waters.

World distribution of the tiger shark. Map © Chondrichthyan Tree of Life

Tiger sharks are considered mostly nocturnal predators, frequently preying at dawn and dusk, but are also known to hunt during daylight hours. They are opportunistic predators and are known to feed on just about anything they encounter. They typically spend their days in deeper water, and at night come closer to the surface and near shore to forage. They are well known for following fishing boats or even ships that discard fish or garbage overboard.

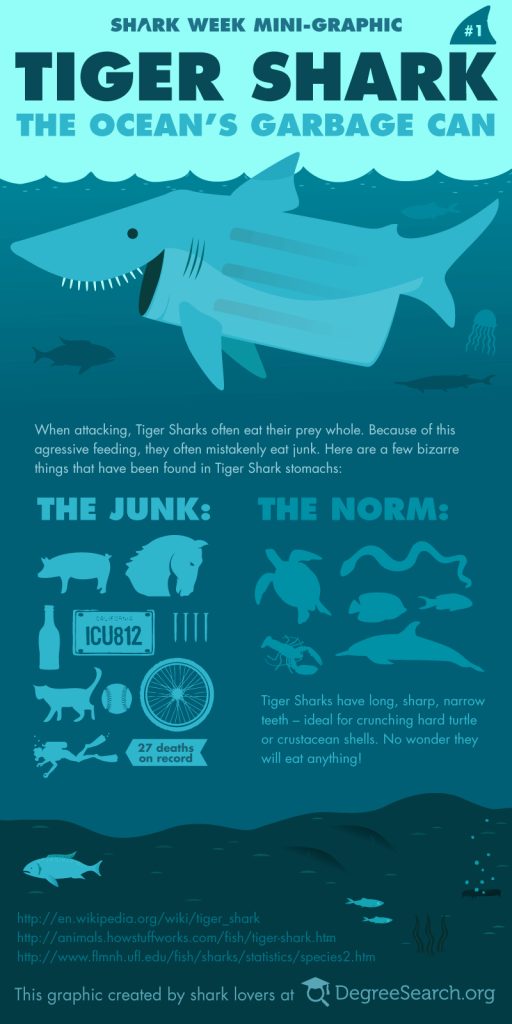

Tiger sharks have been called (disrespectfully) the ‘garbage cans of the sea’ because refuse is often found in the stomachs of sharks caught in harbors and river inlets. One large female caught off the north end of the Red Sea contained two empty cans, a plastic bottle, two burlap sacks, a squid, and an 8 inch fish. There are other old records of weird items in shark stomachs, such as a barbie, a bible, an anchor, a suit of armor, tires, and an unexploded bomb. Some of their food choices may be digested but Tiger sharks and many other sharks have the adaptation to evert their stomachs and discharge indigestible items.

Hawai’i Movements

In Hawai’i these sharks spend much of their time in the northwest Hawaiian Islands (also known as the Papahānaumokuākea, especially around French Frigate Shoals (Hawaiian: Kānemilohaʻi), where they feed on sea turtles, fledging albatross and monk seals. They also forage on dolphins, dead whales and large fish like trevally. Tracking studies using tags have identified a partial migration of tiger sharks within the Hawaiian Islands. In a 2013 study by the University of Hawai’i tracked tagged tiger sharks over several years in Hawai’i. The scientists predicted that 25% of mature females swim from the remote French Frigate Shoals to the main Hawaiian Islands each fall, potentially to give birth. However, some females in the main Hawaiian Islands remain at those islands, while others leave and swim away from the islands, traveling long distances. One shark tagged in the Hawaiian Islands was caught by fishermen off the coast of Mexico.

It is believed that nursery and pupping areas for this species are in the main Hawaiian Islands, with most observed in Maui and Oahu. Some sharks swim to other islands that are correlated with specific environmental conditions such as water temperature.

Anecdotally, the arrival of the pregnant females is supported by recreational diver/ photographers in Kona who contribute to photographic databases, and is corroborated by local Hawaiian investigators. A long term study by native Hawaiian Kaikea Nakachi emulates traditional Hawaiian practices of the kahu manō, (shark keepers). Using non-invasive approaches to develop, assess, and validate photo-ID methodology the Hawaiian’s apply a respectful technique (Pono) for tiger shark research in Hawaiʻi. The team identified 69 individual tiger sharks in West Hawaiʻi over 6 years between 2005-2021. The researchers also observed the same individual male shark and another female shark in West Hawai’i for over 16 years, indicating that these sharks live longer than originally estimated.

Shark Attacks

While the tiger shark ranks second on the list of number of recorded shark attacks on humans, behind the great white shark, such attacks are few and very seldom fatal. Known as Mano Niuhi in Hawaiian, these sharks are well documented in oral history and Hawaiian cultural lore. There are between two to four shark bites in Hawaiian waters every year, most on the islands of Oahu and Maui.

“PUA KA WILIWILI, NANAHU KA MANŌ”

The Hawaiian saying relates to the time when the Wiliwili tree flowers bloom corresponds with an increased frequency of manō (sharks biting humans. Traditional Hawaiian stories warn of an increased danger of shark bites in the fall, from September to November, a prophesy that holds true today.

Classification

Tiger sharks were once thought to be a relatively modern species. However, a 2021 study of fossilized shark teeth identified the relatives of Tiger sharks dating back about 56 million years. Based on these fossil teeth, over 22 extinct tiger shark species have been described. They comprise 22 recognized extinct species with only one living species to date. The oldest fossils of the modern tiger shark date to the Middle Miocene, around 13.8 million years ago.

The tiger shark is a member of the larger Order Carcharhiniformes, a group with over 270 species, but they are a family unto themselves. Until recently, Tiger sharks were included in the Requiem shark family, the Charcharhinidae. In 2021, tiger sharks were separated from the Requiem shark family into a newly designated family, the Galeocerdonidae, in which it is the only species. This reclassification led to their unforeseen elimination of protection under CITES Appendix II in 2022 when the entire family of requiem sharks were listed.

Threats

Killed as bycatch in net and longline fisheries, and for the shark fin trade, this species has been on the decline worldwide. Last assessed in 2019, the species is listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, as Near Threatened globally. One recent study by Chapman et al identifying shark fins in Hong Kong, found tiger sharks represented almost 10 percent of the dried fin trade. The authors also determined that internationally threatened species of sharks represented almost 71% of the fin trade in the study, with endangered sharks like hammerhead sharks bringing the highest prices.

These sharks are also targeted for sport. A July 2023 shark tournament record landed a 1019 pound tiger shark female in Alabama. The world record landed a 1,780-pound tiger shark off the coast of Ulladulla, Australia in 2004. These sharks are also killed in vendetta killings, such as occurred in Egypt this summer, following two human fatalities. Tiger sharks are also killed in beach safety programs and culls. In one West Australian cull, at least 75 percent of the sharks killed on baited drum lines were tigers.

Loss of habitat and climate change are also impacting this primarily coastal shark, especially around coral reef ecosystems. One study showed an alarming 71% decline of the species off Queensland Australia, despite the absence of a targeted fishery. Another study in the NW Atlantic found that tiger sharks’ seasonal distribution has expanded over the last decades, making them more vulnerable to fishing. Warm waters are shifting the NW Atlantic population poleward, extending their range to the north, and possibly causing them to abandon coral reef habitat impacted by global warming and marine heatwaves like the one in summer 2023.

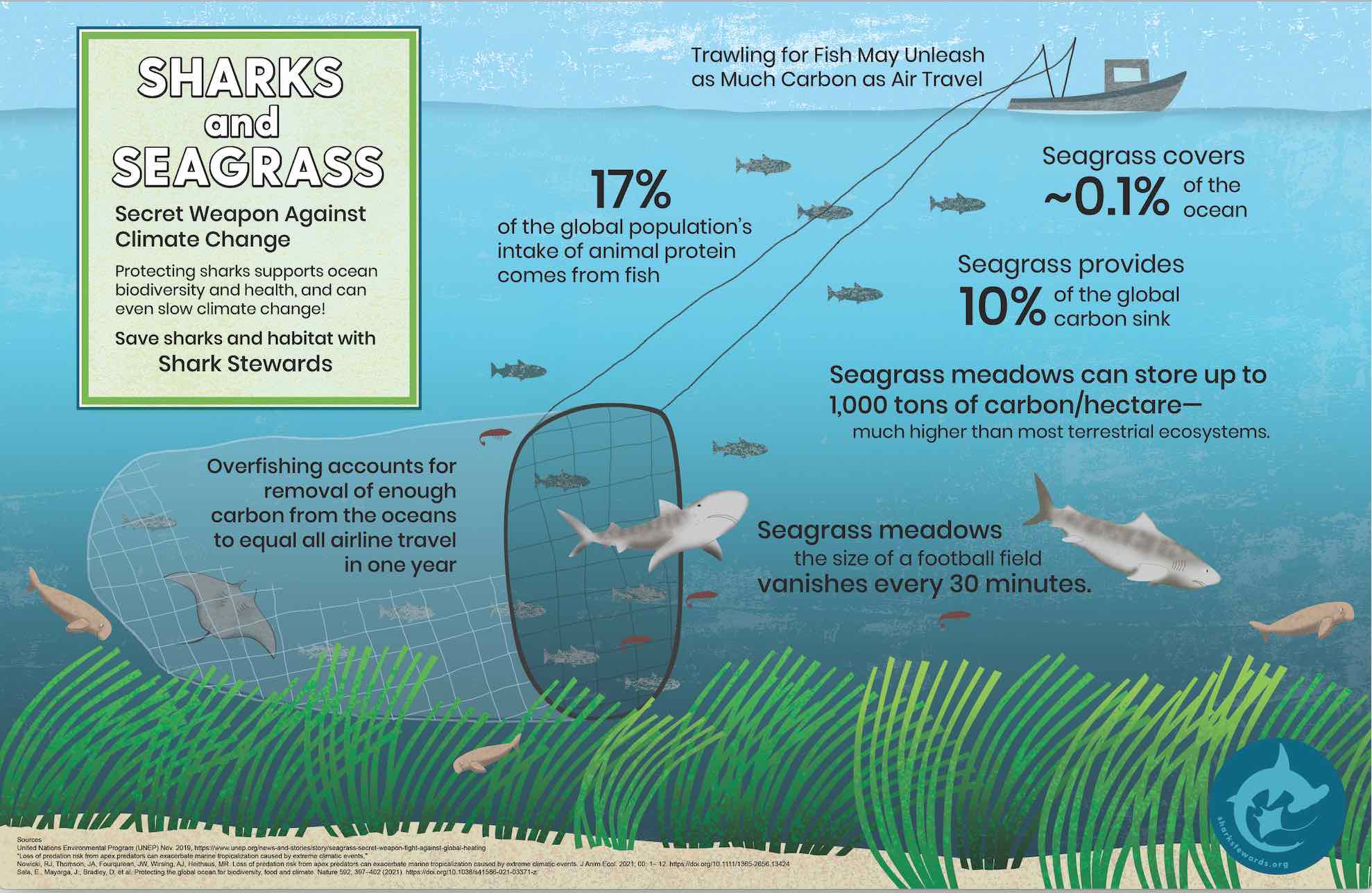

However, studies in Shark Bay Australia have demonstrated that the presence of tiger sharks are crucial to the health of the seagrass marine ecosystem. By keeping grazers like dugongs and sea turtles in check they shape the prey species foraging behavior, tiger sharks in Shark Bay help the seagrass meadows thrive. Flourishing seagrass meadows supports many species and store twice as much CO2 per square mile as forests typically do on land. Thus, saving tiger sharks might just help offset climate change!

In Hawaii, tiger sharks are considered to be sacred ‘aumākua (ancestor, guardian spirits) by some Hawaiian families. Because of this strong cultural connection, Hawaii has been a leader in shark protection including the complete ban on fishing sharks commercially and recreationally.

The respect, and even reverence for sharks by native people in Hawai’i can set the example for protection of these magnificent and important marine predators, and with hope, inspire protection for sharks and marine ecosystems around the world.

References

Compagno, L., Dando, M., & Fowler, S. (2005) A Field Guide to the Sharks of the World. London: Harper Collins Publishers Ltd.

Türtscher, J., López-Romero, F., Jambura, P., Kindlimann, R., Ward, D., & Kriwet, J. (2021). Evolution, diversity, and disparity of the tiger shark lineage Galeocerdo in deep time. Paleobiology, 47(4), 574-590. doi:10.1017/pab.2021.6

SAF Statistics on Attacking Species of Shark”. International Shark Attack File. Florida Museum of Natural History University of Florida. Archived from the original on 2012-08-31. Retrieved 2020-07-20.

Y. P. Papastamatiou, C. G. Meyer, C. Carvalho, J. J. Dale, M. R. Hutchinson, and K. N. Holland, tentatively scheduled for publication in Ecology 94(10), October 2013. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/12-2014.1

Ferreira, L.C.; Simpfendorfer, C. (2019). “Galeocerdo cuvier”. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T39378A2913541. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T39378A2913541.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

Christopher J. Brown et al. Life-history traits inform population trends when assessing the conservation status of a declining tiger shark population, Biological Conservation (2019). DOI: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108230

Diego Cardeñosa, Stanley K. Shea, Huarong Zhang, Gunter A. Fischer, Colin A. Simpfendorfer, Demian D. Chapman First published: 11 July 2022 https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12910 Two thirds of species in a global shark fin trade hub are threatened with extinction: Conservation potential of international trade regulations for coastal sharks Conservation Letters

Nakachi Kaikea I. 2021 Heeding the History of Kahu Manō: Developing and Validating a Pono PhotoIdentification Methodology for Tiger Sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier) in Hawaiʻi, A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Tropical Conservation Biology and Environmental Science Graduate Program University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo

Nowicki RJ, Thomson JA, FourqureanJW, Wirsing AJ, Heithaus MR. Loss of predation risk from apex predators can exacerbate marine tropicalization caused by extreme climatic events. J Anim Ecol. 2021;90:2041-2052. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13424

Neil Hammerschlag et al 2022 Ocean warming alters the distributional range, migratory timing, and spatial protections of an apex predator, the tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier)

https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16045

Pua ka Wiliwili, Nanahu ka Manō: Understanding Sharks in Hawaiian Culture, Noelani Puniwai University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa 7-1-2020